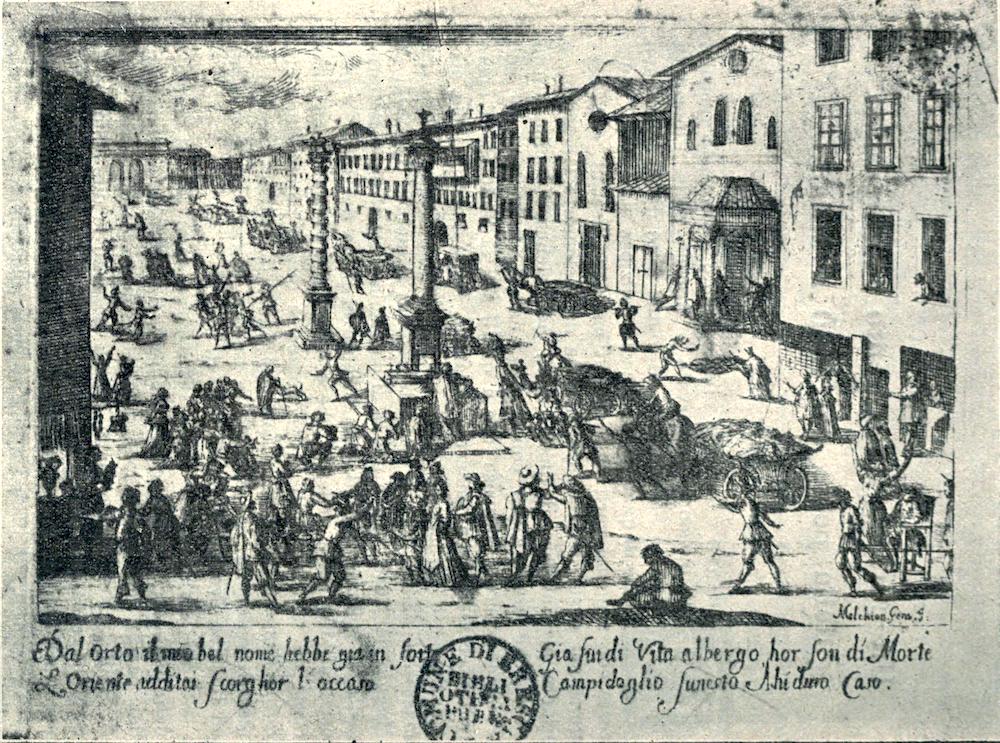

Accusing the Anointers in the Great Plague of Milan in 1630, a scene from Manzoni’s The Betrothed, by Gallo Gallina. Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0).

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

Considered Italy’s most famous novel, Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed, first published in 1827, is set in northern Italy in 1628, when the region was under Spanish rule. The novel follows Renzo and Lucia, who are surprised to find their planned marriage has been forbidden by the local baron, Don Rodrigo, who wants Lucia for himself. Renzo and Lucia flee their village and are separated for most of the novel. In 1630 they finally reunite in Milan, after Renzo learns that Lucia is in the lazaretto, a church used to house sixteen thousand victims of the bubonic plague, which was sweeping through northern and central Italy at the time.

Before Renzo and Lucia reunite, Manzoni leaves his characters behind to devote several chapters to the 1630 plague outbreak in Milan, based largely on Giuseppe Ripamonti’s 1640 history of the epidemic. Manzoni emphasizes the failure of the city’s Spanish rulers to contain the crisis but also places significant blame on the people of Milan for their refusal to recognize the plague for what it was or to take proper measures to protect themselves. The excerpt below, adapted from Daniel J. Connor’s 1924 translation, explains how the city came to understand the truth of its predicament.

Gradually even the obstinacy with which the populace had denied the existence of a plague abated and disappeared as the disease went on spreading—always by means of contact and association. The disillusionment became more pronounced when the evil, after having been confined for a time to the poorer classes, began to attack persons of greater prominence. The case of Settala, the physician-in-chief, was the one that attracted the most attention at the time and calls for special mention even now. Did his fellow citizens at last concede that the good old man was right? Heaven alone knows. What we do know is that he contracted the illness, together with his wife, his two sons, and seven members of the household. He and one son survived; the rest died. “Such fatalities,” says physician Alessandro Tadino, “happening to noble families within the city itself disposed both gentle and simple to reflect, and skeptical doctors and the ignorant, presumptuous rabble began equally to purse the lips, set the jaw, and arch the eyebrows.”

Those who had so long and so doggedly pooh-poohed the idea that disease in embryo lurked nearby and might be transmitted by natural instrumentalities and work havoc, being now unable to dispute the fact of such transmission any longer and unwilling to attribute it to these obvious instrumentalities (which would have been the confession at once of great fallibility and of great blameworthiness), were all the more inclined to discover some other instrumentality at work and to accept the first theory offered.

Unfortunately one was furnished ready-made by the commonly received ideas and traditions, then prevalent not only in Italy but throughout Europe, of the arts of black magic and of conspiracies to disseminate plague by means of infectious poisons and sorcery. Identical or similar practices had been assumed and were believed to exist at other periods, specifically at the time of the last plague, fifty years further back. This general presumption was invested with additional plausibility by a fact that had happened the year before. The governor had received a dispatch, countersigned by King Philip IV, warning him to be on the lookout for four Frenchmen, suspected of disseminating poisonous and disease-bearing ointments, who had escaped from Madrid. The governor had communicated the dispatch to the senate and the board of health; no further heed was apparently paid to the matter at that time. But with the plague breaking out and coming into recognition in the meantime, the memory of the royal admonition may have confirmed an already gathering suspicion of felonious treachery at the bottom of recent developments or may even have given rise to the suspicion originally.

But two incidents, one occasioned by blind, unreasoning fear, the other by some incomprehensible perversity, were the factors that changed this vague surmise of a possible felony into a well-defined suspicion, and in some minds a certainty, of positive felony and a very actual conspiracy against the public weal. Certain persons who happened to be in the cathedral on the evening of May 17 fancied they saw men engaged in smearing some ointment over a scaffolding that served as a partition between the two sexes. Responding to a summons from the frightened witnesses, the president of the board of health hastened to the scene with four subalterns of his department. They inspected the scaffolding, the benches, and the holy-water stoups without finding any evidence of the alleged crime, but out of tenderness for other people’s imaginations and “more to abound in caution than for any real necessity,” they judged a scrubbing to be all that was required.

That did not prevent the victims of the ignorant suspicion of poisoning from lugging the scaffolding and a number of benches out into the street during the night. The sight of all this lumber piled up in the square inspired a great panic in the populace, for whom a fact so easily resolves itself into an argument. It forthwith became a matter of general report and credence that not only the benches and walls of the cathedral but even the bell ropes had been anointed. Nor was it said only at the time. All the chronicles (some of them written by contemporaries many years after the event) that mention the occurrence speak of it in terms of equal assurance, and the true history of the episode would be left to conjecture were it not revealed in a letter from the board of health to the governor that is still preserved in the archives of San Fedele. It is this document we quote from throughout.

The next morning a still stranger and more significant spectacle met the gaze of the citizens and furnished fresh matter for speculation. Doors and housefronts all over the town were daubed with long streaks of some dirty yellow filth, as if it had been applied with a sponge. Whether it was the act of some insane joker who delighted in making the consternation louder and more general or the result of a more criminal intention still, aiming at increasing the public confusion, or from whatever motive it proceeded, the fact itself is so well attested that it would be less reasonable to attribute it to the hallucination of the many than to the mischievousness of a few; particularly since it was not the first nor the last time that such a thing happened. Ripamonti, who frequently ridicules, and more frequently deplores, the public infatuation in this matter of anointings, avers that in this instance he saw the smears and describes them in detail.

The members of the board of health relate the matter in the same terms used by Ripamonti. They speak of visiting the scene, of making experiments on dogs with the matter employed in the defilement, and of the absence of any evil consequences. They add that, in their judgment, “this temerity, such as it has been set forth, proceeded rather from insolence than from any wicked intent”—a reflection that even today vindicates their calmness of mind, enabling them thus not to see what did not exist. Other contemporary records in relating the occurrence mention that the anointing was ascribed by many at the time to jocularity or eccentricity.

I have thought it not amiss thus to bring together and preserve these details of a celebrated superstition, some of which were but little known and some entirely forgotten; because the most interesting, as well as the most useful, lesson to be learned from error, especially endemic error, appears to me to consist in following its successive stages and in ascertaining the guise under which it gained admittance into people’s minds and the sophistries by which it finally established its sovereignty over reason.

The city, which had been nervous before, now went frantic. Householders went about scorching the bedaubed areas with burning straw. Passersby stopped and looked on, appalled, horror-struck. Strangers, liable to suspicion by the very fact of their being strangers and being easily recognizable by their garb, were arrested on the street by civilians and brought before magistrates. Interrogations were instituted and examinations made of captives, captors, and witnesses. No one was found guilty; people’s minds were still capable of hesitating, of examining evidence, of comprehending the obvious. The board of health issued a proclamation, promising immunity and a reward to whosoever informed against the author or authors of the transaction:

Deeming it impolitic in any event that such a misdemeanor should by any means go unpunished, especially in these times of danger and public alarm, we have, for the greater comfort and tranquility of the people and to extort information on the subject, this day issued a proclamation…

But there is no hint, no clear hint at any rate, in the proclamation itself of the reasonable and reassuring conjecture they submitted to the governor—an omission that denotes at once the fury of the popular prejudice and the pliancy of the official character, which was more than commonly reprehensible because it was fraught with more than common possibilities of mischief.

While officialdom was delving for the truth, the man on the street, as often happens, was in full possession of it. Of the faction who accepted the hypothesis of anointings, some maintained that it was a revenge engineered by Don Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordova for the insults inflicted on him while retiring, some claimed that it was a scheme of Cardinal Richelieu to depopulate Milan and seize it without a struggle, while still others, for reasons that still remain apocryphal, would have the culprit to be the Count of Collato, Wallenstein, or even this, that, or the other nobleman of Milan itself. There were not wanting supporters of the view already alluded to, that the whole affair was nothing but a wanton joke attributable to students, nobles, or officials to whom the siege of Casale was a cause of annoyance. As time wore on and signs of the expected aftermath of sudden and general disease and death failed to develop, this first paroxysm of fright gradually abated and the occurrence fell, or seemed to fall, into oblivion.

There never ceased to be, all this while, a certain number of persons who were still unconvinced of the existence of a plague. And because, in the lazaretto as well as in the city at large, a certain number of victims recovered, “it was said” (the final arguments of a forlorn view checkmated by evidence are always curious)—“it was said by the generality and by many doctors who still clung to their prepossessions that it was not true pestilence, else all would have perished.”

To banish all doubt the board of health resorted to an expedient proportioned to the needs that elicited it, a spectacular object lesson the conditions were desperate enough to demand and at the same time to supply. During the festivities of Pentecost there was one day when it was the custom of the townspeople to flock to the Cemetery of St. Gregory, outside the Porta Orientale, to pray for the victims of the former epidemic who were buried there and, profiting by the occasion, to combine diversion and display with devotion and deck themselves out in holiday attire. On that day the deaths from the plague included one entire family. At the very height of the celebration, through the press of coaches and horsemen and pedestrians, the corpses of this ill-fated family were by order of the board of health loaded on a cart and conveyed to the cemetery in question stark naked, that all might see the manifest signs of pestilence on their bodies. An exclamation of repugnance and terror greeted the ghastly display. A prolonged murmur swelled like an ever-widening ripple ahead of the cart’s advance, and another marked the area of horror it constantly left in its wake. The plague was believed in more firmly; but anyhow it acquired credence of itself, and this same gathering served not a little to give impetus to its spread.

The developments, therefore, might be scanned thus: At the start no question of a plague, absolutely none—preposterous. The very word is tabooed. Then, pestilent fevers, with an oblique implication of the idea of plague introduced by the adjective. Then a simulated plague. The plague, if you will, but with qualifications; that is, not true plague, but something for which another name is lacking. Finally, plague without any doubt or quibble. But straightaway another idea, that of poisoning and sorcery, is tacked on, which confuses and neutralizes the plain meaning of the word itself, which can now no longer be suppressed.

Read the other entries in our series: Heinrich Heine, George Eliot, Samuel Pepys, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Thomas Mann, Jack London, John Keats, Giovanni Boccaccio, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Daniel Defoe, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.